A vaginal examination is a systematic medical assessment that evaluates the external and internal female reproductive structures to diagnose conditions and screen for abnormalities. This essential clinical procedure allows healthcare providers to examine the vulva, vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries through visual inspection and palpation techniques. The examination serves as a critical diagnostic tool for identifying infections, abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain, masses, and various gynecological conditions that may otherwise go undetected.

Healthcare providers perform vaginal examinations for both symptomatic patients experiencing issues like abnormal discharge, pelvic pain, or irregular bleeding, and as part of routine screening in certain circumstances. The procedure involves external assessment of the vulvar area, followed by internal examination using a speculum to visualize the cervix and vaginal walls, and concludes with a bimanual examination to evaluate the pelvic organs. Understanding the components and purpose of this examination helps patients feel more prepared and comfortable during the process.

The examination requires careful preparation, clear communication between provider and patient, and systematic assessment techniques to ensure accurate diagnosis and patient comfort. Modern guidelines emphasize the importance of obtaining proper consent, explaining each step of the procedure, and tailoring the examination to the patient’s specific clinical needs and comfort level.

Key Takeaways

- Vaginal examinations diagnose gynecological conditions through systematic evaluation of external and internal reproductive structures

- The procedure includes external assessment, speculum examination, and bimanual palpation to evaluate all pelvic organs

- Proper patient communication and preparation are essential for accurate diagnosis and patient comfort during the examination

Contents

1. Principles and Indications of Vaginal Examination

2. Preparation and Patient Communication

3. External Genital and Vulval Assessment

- Inspection of Vulva

- Assessment for Pathologies

- Palpation of Inguinal Lymph Nodes

- Evaluation for Masses and Prolapse

4. Speculum and Cervical Assessment

- Performing Speculum Examination

- Evaluation of Cervix and Vaginal Walls

- Collection of Swabs and Samples

Principles and Indications of Vaginal Examination

Vaginal examination serves as a fundamental diagnostic tool in gynecological and obstetric practice, requiring specific clinical indications and proper understanding of pelvic anatomy. The procedure involves careful assessment of internal and external genital structures while maintaining patient comfort and dignity.

Purpose and Clinical Indications

Vaginal examination provides essential diagnostic information for numerous gynecological conditions. The procedure allows healthcare providers to assess the cervix, vagina, uterus, and surrounding structures through direct palpation and visualization.

Primary diagnostic indications include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, including menstrual irregularities and postmenopausal bleeding

- Pelvic pain assessment, particularly dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia

- Abnormal vaginal discharge evaluation and infection screening

- Pelvic mass detection and characterization

The examination proves essential for obstetric care during labor assessment. Healthcare providers use vaginal examination to diagnose labor onset, monitor cervical dilation, and assess fetal presentation and position.

Additional clinical situations requiring examination include suspected retained foreign bodies, trauma assessment, and evaluation of anatomical abnormalities. The procedure also supports pre-procedural assessment before IUD insertion or other gynecological interventions.

In OSCE settings, candidates must demonstrate proper technique while explaining indications clearly to standardized patients.

Contraindications and Precautions

The primary absolute contraindication for vaginal examination is lack of patient consent. Healthcare providers must obtain informed consent and respect patient autonomy regarding this intimate procedure.

Relative contraindications require careful clinical judgment. These include active vaginal bleeding of unknown origin, suspected cervical spine injury, and certain pregnancy complications where examination might cause harm.

Special precautions apply for:

- Patients with history of sexual trauma or abuse

- Adolescent patients requiring age-appropriate communication

- Pregnant patients with threatened preterm labor

Healthcare providers must consider patient anxiety and discomfort as significant factors. The examination can cause physical discomfort, emotional distress, and feelings of vulnerability, particularly in patients with previous traumatic experiences.

Proper patient preparation and clear communication help minimize psychological impact. Providers should explain each step of the procedure and allow patients to maintain some control during the examination process.

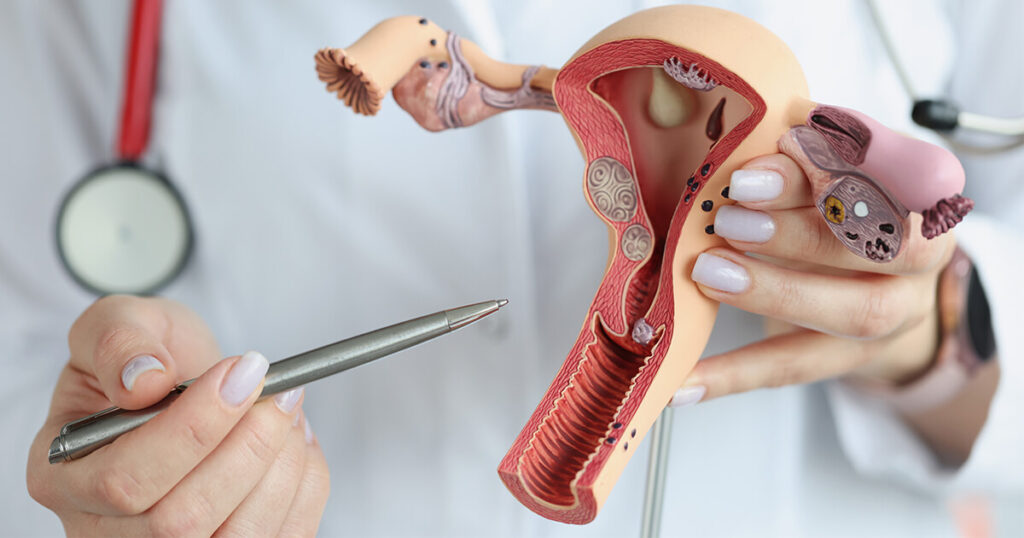

Relevant Anatomy

Understanding pelvic anatomy is crucial for effective vaginal examination. The external genitalia include the vulva, labia majora and minora, clitoris, and vaginal introitus.

The vagina extends 8-10 cm from the introitus to the cervix. Vaginal rugae create the characteristic textured surface that examiners palpate during digital examination. Normal vaginal pH ranges from 3.5 to 4.0.

Key internal structures assessed include:

- Cervix: Fibromuscular organ connecting uterus to vagina

- Uterus: Triangular muscular organ, approximately 7 cm in length

- Adnexa: Ovaries and fallopian tubes, typically 2-3 cm in size

The cervix protrudes into the vaginal vault and contains the external os. During examination, providers assess cervical position, consistency, and dilation status.

Bartholin glands located at 4 and 8 o’clock positions require evaluation for enlargement or tenderness. The rectovaginal septum and pelvic floor muscles provide additional anatomical landmarks during bimanual examination.

Proper anatomical knowledge enables accurate identification of normal variants versus pathological findings during clinical examination.

Preparation and Patient Communication

Proper preparation involves establishing clear communication, obtaining appropriate consent, and ensuring patient comfort through correct positioning and sterile technique. Essential elements include chaperone presence, proper equipment setup, and infection control measures.

Chaperone and Consent

A chaperone must be present during all vaginal examinations. The healthcare provider should explain this requirement to the patient and obtain permission for the chaperone’s presence.

The examination should be explained using clear, patient-friendly language. The provider should describe what the procedure involves, including the use of fingers for internal examination and potential mild discomfort.

Consent must be obtained before proceeding. Patients should be informed they can stop the examination at any point. The provider should ask about current pain levels and possible pregnancy before beginning.

Key questions include confirming the patient’s comfort level and addressing any concerns. The patient should be given time to ask questions and receive clear answers about the procedure.

Patient Positioning

Patients should be instructed to empty their bladder before the examination to reduce discomfort and improve palpation accuracy. This step is essential for optimal examination conditions.

The modified lithotomy position is the standard positioning technique. Patients should draw their ankles toward their buttocks, keep feet flat on the examination table, and allow their legs to fall open naturally.

Privacy during positioning is crucial. Patients should be provided with appropriate draping and given privacy to undress. The provider should ask permission before re-entering the examination room.

Proper positioning ensures adequate visualization and access while maintaining patient dignity and comfort throughout the procedure.

Equipment and Infection Control

Essential equipment includes sterile gloves, lubricant, and paper towels. All items should be gathered before beginning the examination to avoid interruptions during the procedure.

Hand hygiene must be performed before donning gloves. Non-sterile gloves are typically sufficient for routine examinations. Fresh gloves should be used for each patient encounter.

Water-based lubricant should be applied to the examining fingers to minimize patient discomfort. Adequate lighting must be ensured for proper visualization of anatomical structures.

Equipment disposal follows standard clinical waste protocols. Used materials should be disposed of immediately after examination completion to maintain infection control standards.

External Genital and Vulval Assessment

External genital examination involves systematic inspection of the vulva and surrounding structures to identify normal anatomy and detect pathological changes. Assessment includes evaluation of the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, urethral meatus, vaginal introitus, and perineum for signs of infection, malignancy, structural abnormalities, and pelvic organ prolapse.

Inspection of Vulva

The clinician begins by inspecting the mons pubis for hair distribution patterns, which may indicate hormonal imbalances or developmental abnormalities. Normal adult female hair distribution forms an inverted triangle pattern.

Labia majora and minora require careful examination for symmetry, color changes, and structural abnormalities. The examiner looks for signs of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women, characterized by thinning, pale tissue and reduced elasticity.

Scarring from previous trauma, episiotomy, or female genital mutilation (FGM) should be documented. FGM may present as partial or complete removal of external genital structures with associated scarring patterns.

The clitoris and urethral meatus are inspected for anatomical variations, inflammation, or discharge. The vaginal introitus is examined for patency and any obstructing lesions.

Assessment for Pathologies

White lesions such as lichen sclerosus appear as porcelain-white patches with potential scarring and architectural distortion. Leukoplakia presents as thickened white plaques that require biopsy evaluation.

Infectious conditions manifest differently based on causative organisms. Candidiasis produces cottage cheese-like discharge with vulval erythema and pruritis. Herpes presents as painful vesicles progressing to shallow ulcers.

Bacterial vaginosis typically causes malodorous discharge without significant vulval changes. Chlamydia and gonorrhoea may present with purulent discharge and urethral inflammation.

Skin conditions include folliculitis with inflamed hair follicles, molluscum contagiosum showing characteristic umbilicated papules, and genital warts appearing as flesh-colored or pigmented papillomatous lesions.

Bartholin’s cysts present as unilateral swellings at the posterior labia majora. Bartholin’s glands may become infected, forming painful abscesses requiring drainage.

Palpation of Inguinal Lymph Nodes

Inguinal lymph nodes are palpated bilaterally to assess for lymphadenopathy associated with vulval pathology or systemic conditions. Normal lymph nodes are typically non-palpable or small, mobile, and non-tender.

Acute infections such as herpes, bacterial infections, or cellulitis commonly cause tender, enlarged inguinal lymph nodes. The examiner palpates both superficial and deep inguinal node chains systematically.

Vulval cancer or vulval malignancy may cause firm, fixed, or matted lymph nodes. Persistent lymphadenopathy without obvious infectious cause requires further investigation including possible biopsy.

Chronic conditions like recurrent infections or inflammatory disorders may cause mild, persistent lymph node enlargement. Documentation should include size, consistency, mobility, and tenderness of palpable nodes.

Evaluation for Masses and Prolapse

Cyst formation beyond Bartholin’s cysts includes sebaceous cysts, inclusion cysts, and Skene’s gland cysts. Each requires differentiation based on location, consistency, and associated symptoms.

Varicosities may develop secondary to chronic venous disease, pregnancy, or pelvic congestion. These appear as dilated, tortuous veins typically along the labia majora or perineum.

Vaginal prolapse assessment involves examining the vaginal introitus for bulging or protrusion of vaginal walls. The examiner may ask the patient to perform Valsalva maneuver to assess prolapse severity.

Vulval malignancy presents as irregular masses, persistent ulceration, or asymmetric growths. Any suspicious lesion requires prompt referral for specialist evaluation and possible biopsy.

Speculum and Cervical Assessment

The speculum examination provides direct visualization of the cervix and vaginal walls for diagnostic assessment. This procedure enables collection of specimens for testing and identification of pathological conditions.

Performing Speculum Examination

The speculum is inserted with blades closed, typically positioned sideways initially before rotation to vertical alignment. Proper lubrication reduces patient discomfort during insertion.

Once inserted, the blades open gradually until optimal cervical visualization occurs. The locking mechanism secures the speculum position to maintain consistent viewing access.

Key insertion steps:

- Separate labia with non-dominant hand

- Insert closed speculum at 3 or 9 o’clock position

- Rotate handle upward after insertion

- Open blades slowly until cervix visible

- Secure locking nut to maintain position

Patient positioning in modified lithotomy facilitates examination access. Adequate lighting ensures clear visualization of anatomical structures.

The speculum examination requires gentle technique to minimize discomfort. Patients should be informed they may experience mild pressure sensations during the procedure.

Evaluation of Cervix and Vaginal Walls

Cervical assessment focuses on the external os, surface characteristics, and surrounding tissue appearance. A normal cervix appears pink with smooth contours and closed os in non-pregnant patients.

Cervical abnormalities include:

- Ectropion around the os

- Ulcerations or erosions

- Masses or growths

- Scarring from previous procedures

Cervical ectropion presents as red areas around the external os where columnar epithelium extends onto the vaginal cervix. This condition may cause post-coital bleeding.

CIN and early cervical cancer may appear as white or red patches on the cervical surface. Advanced disease presents with visible ulceration or tumor formation.

Vaginal wall inspection identifies discharge characteristics, atrophic changes, or foreign bodies. Abnormal vaginal discharge varies by etiology – bacterial vaginosis produces thin, fishy-smelling discharge while candidiasis creates thick, curd-like secretions.

Collection of Swabs and Samples

Endocervical swabs collect specimens from the cervical canal for infection screening including chlamydia and gonorrhoea. The swab inserts into the os and rotates gently before removal.

Vaginal swabs sample the posterior fornix or vaginal walls for bacterial cultures and microscopy. These specimens help diagnose bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, and trichomoniasis.

Sample collection sequence:

- Endocervical swab for STI testing

- Vaginal swab for microscopy

- Additional specimens as indicated

Cervical cytology requires specific technique using a spatula and brush combination. The spatula samples the ectocervix while the brush collects endocervical cells.

HPV testing may accompany cytology collection or serve as primary screening. Abnormal results require colposcopy referral for detailed cervical examination.

Proper specimen labeling and transport maintains sample integrity. Each specimen requires appropriate transport medium and timely laboratory processing.

Bimanual Vaginal and Pelvic Examination

The bimanual exam combines internal vaginal palpation with abdominal examination to assess uterine size, position, mobility, and detect adnexal masses. This technique enables systematic evaluation of pelvic structures for pathology including ovarian cysts, fibroids, and signs of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Bimanual Technique and Anatomy

The examiner inserts two lubricated fingers of the dominant hand into the vagina while placing the other hand on the lower abdomen. The internal fingers provide support while the external hand applies gentle pressure downward.

Proper positioning involves:

- Patient in lithotomy position with knees flexed

- Examiner seated comfortably at foot of table

- Internal fingers pointing toward the sacrum initially

The cervix feels firm like the tip of the nose and may be positioned centrally or deviated slightly. Normal cervical mobility allows 1-2 cm movement without pain.

The uterus typically measures 6-8 cm in length and feels smooth and mobile. It may be anteverted, retroverted, or in midposition. The fundus should be palpable between the examining hands when the uterus is anteverted.

Assessment for Masses and Tenderness

Systematic palpation evaluates each anatomical region for abnormal findings. The examiner assesses the cervix, uterine body, and bilateral adnexal areas methodically.

Key assessment areas include:

- Cervical motion tenderness (suggests pelvic inflammatory disease)

- Uterine enlargement or irregularity

- Adnexal masses or tenderness

- Pouch of Douglas for nodularity

A pelvic mass may feel firm, mobile, or fixed depending on its origin. Ovarian cysts typically feel smooth and mobile, while fibroids create irregular uterine contours.

Cervical motion tenderness during bimanual exam strongly suggests pelvic inflammatory disease when combined with appropriate clinical symptoms. The examiner notes any pain with cervical manipulation or uterine movement.

Identifying Uterine and Adnexal Pathology

Uterine fibroids create characteristic irregular enlargement with firm, nodular surfaces. The uterus may feel asymmetrical and heavier than normal during bimanual palpation.

Common pathological findings:

- Fibroids: Irregular, firm uterine enlargement

- Ovarian cysts: Smooth, mobile adnexal masses

- Endometriosis: Fixed, tender masses in pouch of Douglas

- Pelvic malignancy: Fixed, irregular masses

Adnexal masses require careful evaluation for size, consistency, and mobility. Normal ovaries are often not palpable, especially in postmenopausal women where any palpable adnexal mass warrants investigation.

The bimanual exam cannot definitively diagnose specific conditions but guides further imaging and testing. Fixed masses or those larger than 5 cm typically require ultrasound evaluation to characterize the pathology further.

Post-Examination Procedures and Differential Diagnosis

Proper post-examination procedures ensure accurate documentation and appropriate follow-up testing based on clinical findings. Laboratory tests including urinalysis and β-hCG help confirm suspected diagnoses, while systematic correlation of examination findings with potential pathology guides treatment decisions.

Documentation and Communication

Accurate documentation forms the foundation of quality gynecological care. The examination record should include detailed findings from external genital inspection, speculum examination, and bimanual palpation.

Essential Documentation Elements:

- Position and appearance of cervix

- Uterine size, position, and mobility

- Adnexal masses or tenderness

- Vaginal discharge characteristics

- Any abnormal findings or lesions

Communication with patients requires sensitivity and clarity. Practitioners should explain findings in understandable terms while avoiding medical jargon. Immediate reassurance about normal findings helps reduce patient anxiety.

For OSCE examinations, candidates must demonstrate proper documentation skills. This includes recording negative findings alongside positive ones and using appropriate medical terminology.

Urinalysis and Laboratory Testing

Laboratory investigations complement clinical examination findings and confirm suspected diagnoses. Urinalysis provides valuable information about urinary tract infections that may cause pelvic pain or abnormal discharge.

Key Laboratory Tests:

- β-hCG testing for pregnancy confirmation in reproductive-age women

- Vaginal swabs for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity testing

- Urine dipstick for nitrites, leukocyte esterase, and protein

- High vaginal swabs for chronic or recurrent symptoms

β-hCG testing is particularly important when patients present with irregular bleeding or pelvic pain. Pregnancy must be excluded before certain treatments or procedures.

Vaginal swabs should be considered for patients with characteristic symptoms, postpartum status, or post-instrumentation findings.

Correlating Findings with Pathology

Clinical examination findings must be systematically correlated with potential pathological conditions. Having differential diagnoses in mind helps focus the examination and guide appropriate investigations.

Common Presentations and Correlations:

- Pelvic pain may indicate ovarian cysts, endometriosis, or pelvic inflammatory disease

- Abnormal bleeding requires assessment for cervical pathology, endometrial disorders, or pregnancy complications

- Vaginal discharge patterns help differentiate between bacterial vaginosis, candidiasis, and sexually transmitted infections

Normal physiological discharge consists of 1-5 mL per 24 hours and appears transparent to white-yellowish. Deviations from this pattern warrant further investigation.

Examination findings should be interpreted within the clinical context. Patient history combined with physical findings creates a comprehensive picture for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning.