Key Takeaways

- Chickenpox spreads easily but usually clears up on its own with proper care.

- Recognizing the rash and managing symptoms early helps prevent complications.

- Vaccination and good hygiene reduce the risk of infection and transmission.

Chickenpox can catch you off guard, especially when your child suddenly develops an itchy rash and a fever. It’s a common childhood illness, but knowing how to handle it calmly makes all the difference. You can manage chickenpox at home safely by recognizing symptoms early, easing discomfort, and preventing it from spreading to others.

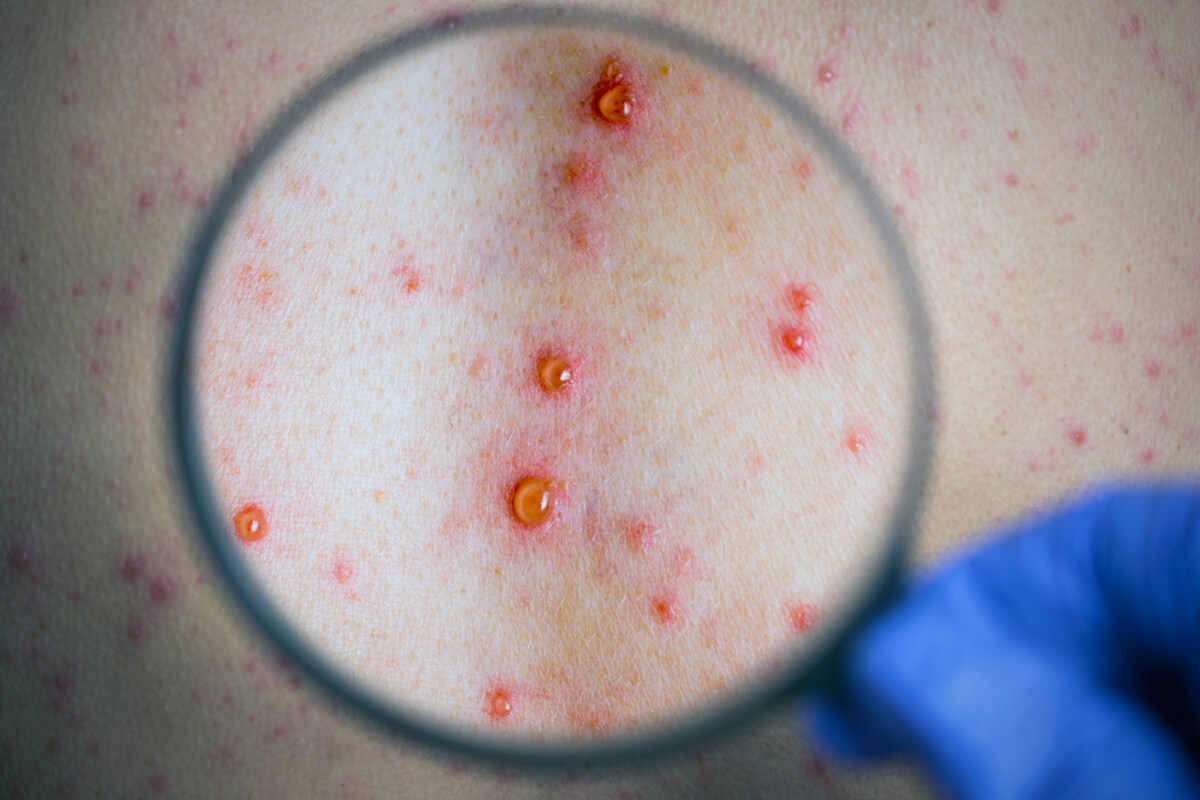

You’ll notice small red spots that turn into fluid-filled blisters before scabbing over. While it usually clears up within a week or two, some children and adults can face complications if their immune system is weak. Understanding how chickenpox spreads helps you protect your family and others who may be more vulnerable.

By learning what to expect and how to care for your child, you can reduce stress and focus on comfort and recovery. Knowing when to seek medical advice ensures you act quickly if symptoms worsen or unusual signs appear.

Contents

1. Understanding Chickenpox and Its Causes

- What Is Chickenpox?

- The Varicella-Zoster Virus

- How Chickenpox Spreads

- Incubation Period and Contagiousness

2. Recognizing Symptoms in Children

- Early Signs and Onset

- Rash Progression and Itching

- Associated Fever and Other Symptoms

- When to Seek Medical Help

3. Treatment and Home Care Strategies

- Managing Fever and Discomfort

- Relieving Itching and Skin Care

- Medications to Avoid

- Hydration and Rest

Vaccination Program

Explore our range of vaccination programs designed for your specific health needs.

Understanding Chickenpox and Its Causes

Chickenpox results from infection with the varicella-zoster virus, which affects people who have not been vaccinated or previously infected. The illness spreads easily through the air or direct contact and follows a clear pattern from exposure to recovery.

What Is Chickenpox?

Chickenpox, or varicella, is a common viral infection that causes an itchy rash and mild fever. You usually see small red spots that turn into fluid-filled blisters before scabbing over. The rash often starts on the face, chest, or back, then spreads to other areas.

Most cases occur in children, but adults can also become infected and may experience more severe symptoms. Common early signs include tiredness, loss of appetite, and irritability.

Although chickenpox is typically mild, it can cause serious complications in infants, adults, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.

Vaccination has greatly reduced the number of chickenpox cases. The vaccine helps your body build immunity without causing the illness. Once you’ve had chickenpox, your body usually develops lifelong immunity.

The Varicella-Zoster Virus

The varicella-zoster virus (VZV) belongs to the herpesvirus family. It infects only humans and remains in your body for life after the first infection. Once you recover, the virus becomes inactive in nerve cells near the spinal cord and brain.

VZV can reactivate years later as shingles (herpes zoster), a painful rash that appears on one side of the body. This reactivation does not mean you have chickenpox again, but it shows that the virus remains dormant in your system.

The virus is fragile outside the body and does not survive long on surfaces. It spreads almost entirely through close contact or airborne droplets rather than contaminated objects.

How Chickenpox Spreads

Chickenpox spreads easily when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, releasing tiny droplets that others breathe in. You can also catch it by touching the fluid from blisters or objects recently contaminated with it.

A person is contagious from 1–2 days before the rash appears until every blister has crusted over. Because the virus spreads so readily, outbreaks often occur in schools, daycare centers, and households.

If you have never had chickenpox or the vaccine, your chance of infection after exposure is very high.

Preventing spread involves staying home until all lesions have scabbed, washing hands frequently, and avoiding close contact with others during the contagious period.

Incubation Period and Contagiousness

The incubation period—the time between exposure and first symptoms—usually lasts 10 to 21 days, most often around two weeks. During this time, the virus multiplies in your body without visible signs.

You become contagious before the rash appears, which makes early isolation difficult. The rash develops over 5–7 days, and new spots can appear for several days.

Once all blisters have dried and crusted, you are no longer contagious.

| Stage: Incubation | |

|---|---|

| Typical Duration | 10–21 days |

| Contagious? | No |

| Stage: Pre-rash (1–2 days) | |

|---|---|

| Typical Duration | 1–2 days |

| Contagious? | Yes |

| Stage: Rash active | |

|---|---|

| Typical Duration | 5–7 days |

| Contagious? | Yes |

| Stage: All lesions crusted | |

|---|---|

| Typical Duration | 1–2 weeks |

| Contagious? | No |

Understanding these timeframes helps you prevent transmission and care for your child safely.

Recognizing Symptoms in Children

Chickenpox often begins with mild, flu-like symptoms before a distinctive rash appears. The illness progresses in stages, from early warning signs to the formation of blisters and scabs, and may include fever, fatigue, and itching that can cause discomfort for your child.

Early Signs and Onset

You may first notice your child feeling tired, irritable, or slightly unwell. Mild fever, headache, and loss of appetite often appear one to two days before the rash. These early signs can resemble a common cold, which makes it easy to miss the initial stage of chickenpox.

During this time, your child is already contagious. The virus spreads through droplets from coughing or sneezing and through direct contact with the skin lesions once they appear.

Keep your child home from school or childcare as soon as symptoms begin. Early recognition helps reduce the risk of spreading the infection to others, especially infants, pregnant people, and those with weakened immune systems.

Rash Progression and Itching

The rash usually starts on the torso or scalp before spreading to the face, arms, and legs. It begins as small red spots that quickly develop into fluid-filled blisters. Over several days, new spots appear in waves as older ones crust over.

Itching can be intense. Encourage your child not to scratch to avoid bacterial infection or scarring. You can help by keeping fingernails short and using calamine lotion, oatmeal baths, or a mild antihistamine if recommended by your pediatrician.

A simple timeline can help track the rash:

| Stage: Red spots | |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Flat or raised |

| Duration | 1–2 days |

| Care Tip | Keep skin clean |

| Stage: Blisters | |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Clear fluid |

| Duration | 2–3 days |

| Care Tip | Avoid scratching |

| Stage: Scabs | |

|---|---|

| Appearance | Dry, crusted |

| Duration | 5–7 days |

| Care Tip | Continue gentle bathing |

Associated Fever and Other Symptoms

Along with the rash, your child may develop a fever between 100°F and 102°F (37.8°C–38.9°C). The fever usually peaks as the rash spreads. Other symptoms can include body aches, sore throat, or general fatigue.

Offer fluids and rest. You can use acetaminophen for fever relief, but avoid aspirin because it increases the risk of Reye syndrome.

In rare cases, complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) can occur, especially in children with weakened immune systems. These are medical emergencies that require immediate attention.

When to Seek Medical Help

Contact your pediatrician if your child’s fever lasts more than four days, exceeds 102°F (38.9°C), or if the rash becomes red, swollen, or painful. These could indicate a bacterial skin infection.

Seek urgent care if your child has difficulty breathing, severe headache, confusion, persistent vomiting, or trouble staying awake. These may be signs of serious complications like encephalitis.

If your child is younger than one year, older than twelve, or has a chronic condition such as asthma or eczema, inform your healthcare provider promptly after exposure or at the first sign of chickenpox.

Treatment and Home Care Strategies

Most children recover from chickenpox at home with supportive care. Managing fever, easing itching, and keeping your child comfortable reduce discomfort and help prevent complications. Careful use of medicines and attention to rest and hydration support a smoother recovery.

Managing Fever and Discomfort

Fever often appears early in chickenpox and can make your child feel tired or irritable. You can give paracetamol (acetaminophen) to reduce fever and ease pain, following age-appropriate dosing instructions. Avoid giving aspirin because it can lead to Reye’s syndrome, a serious condition affecting the liver and brain.

Keep your child cool but not cold. Dress them in lightweight clothing and use a fan or open window for fresh air. Monitor temperature regularly and encourage rest. If fever lasts more than four days, or your child becomes unusually drowsy or breathless, contact a healthcare professional.

Relieving Itching and Skin Care

Itching can be intense and may lead to scratching, which increases the risk of skin infection. Keep your child’s nails short and clean. You can also use cotton gloves at night to prevent scratching during sleep.

Apply calamine lotion or a cool oatmeal bath to calm irritated skin. Some parents find that fragrance-free moisturizers help reduce dryness once blisters begin to heal. Dress your child in loose cotton clothing to limit friction.

If blisters become red, swollen, or filled with pus, see a doctor. These signs may indicate a secondary bacterial infection that needs medical attention.

Medications to Avoid

Certain medicines can worsen chickenpox or increase risks. Aspirin and other salicylate-containing products must be avoided due to the link with Reye’s syndrome. Ibuprofen may also raise the risk of skin infections in some children with chickenpox, so use it only if recommended by a healthcare provider.

Steroids should not be used unless specifically prescribed for another medical reason, as they can weaken the immune system and make the infection more severe. If your child takes immunosuppressive medication for another condition, contact your doctor for tailored advice.

Always check the label of any over-the-counter medicine before giving it to your child. When in doubt, ask a pharmacist or doctor for guidance.

Hydration and Rest

Chickenpox can reduce appetite and cause mild dehydration, especially if fever is present. Offer plenty of fluids such as water, diluted juice, or oral rehydration solutions. For younger children, ice lollies or cold soups can help maintain fluid intake while soothing sore mouths.

Encourage quiet rest and avoid strenuous activity until all blisters have crusted over. Rest helps the immune system fight the virus more effectively.

Keep your child at home until spots have dried to prevent spreading the infection to others, especially newborns, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.

Complications and High-Risk Groups

Chickenpox can lead to secondary infections and, in some cases, affect the brain, liver, or other organs. People with weakened immune systems and pregnant women face higher risks of serious illness and should seek medical advice early if exposed or symptomatic.

Bacterial Skin Infections

Scratching the itchy rash can break the skin and allow bacteria, such as Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, to enter. These bacteria may cause impetigo, cellulitis, or deeper soft-tissue infections.

You might notice redness, swelling, warmth, or pus around healing blisters. Seek medical care if these symptoms appear, as untreated infections can spread quickly.

In rare cases, bacteria can invade deeper layers and cause necrotizing fasciitis, a severe soft-tissue infection requiring urgent treatment. Good hygiene, trimmed nails, and discouraging scratching reduce this risk in children.

Neurological and Organ Complications

Chickenpox can occasionally affect the brain or liver, especially in older children or adults. Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) may cause headache, confusion, vomiting, or difficulty walking. Cerebellar ataxia, a milder form, can cause unsteady movements but usually improves with time.

Hepatitis may develop when the virus affects the liver. This complication is uncommon and often mild but needs monitoring if you have underlying liver disease.

Severe cases can also cause pneumonia, particularly in adults or smokers. If you experience persistent cough, chest pain, or shortness of breath, contact a healthcare provider promptly.

Risks for Immunocompromised Patients

If you or your child have a weakened immune system, chickenpox can progress rapidly and cause serious complications. This includes people receiving chemotherapy, organ transplant recipients, or those with conditions such as HIV/AIDS.

Because the immune system cannot control viral replication effectively, the rash may be more widespread, and fever may last longer. The infection can spread to the lungs, liver, or brain more easily.

Doctors often recommend antiviral medication or varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG) after exposure to reduce severity. Avoid contact with infected individuals until your healthcare provider confirms safety.

Risks During Pregnancy

If you become infected with chickenpox during pregnancy, both you and your baby may face complications. Early pregnancy infection can rarely lead to congenital varicella syndrome, causing limb or eye abnormalities.

In later pregnancy, infection may result in maternal pneumonia, which can be severe and require hospital care.

If you are pregnant and exposed to chickenpox, contact your healthcare provider immediately. You may receive VZIG to lower the risk of severe illness. After birth, newborns exposed near delivery may need close monitoring or antiviral treatment.

Prevention and Vaccination

Vaccination provides the most reliable protection against chickenpox and its complications. Preventive steps also include managing exposure risks for people who cannot be vaccinated, such as those with weakened immune systems or pregnant women.

Chickenpox Vaccine Overview

The chickenpox vaccine (varicella vaccine) helps your child build immunity against the varicella-zoster virus. It is a live, attenuated vaccine that contains a weakened form of the virus, which triggers the body to produce protective antibodies without causing illness.

Two doses provide strong protection. Studies show that one dose prevents about 80–85% of infections, while two doses prevent about 98% of cases. Even if infection occurs after vaccination, symptoms are usually mild with fewer blisters and lower fever.

The vaccine is available as a single-varicella shot or in combination with the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine (MMRV). Both forms are safe and effective. Side effects are typically mild, such as soreness at the injection site or a low-grade fever.

Who Should Be Vaccinated

Children should receive their first dose of the chickenpox vaccine at 12–15 months and a second dose at 4–6 years. Older children, teens, and adults who have never had chickenpox or the vaccine should also be immunized.

Certain groups need special consideration:

- Pregnant women should not receive the vaccine during pregnancy but should get vaccinated before becoming pregnant if not immune.

- Immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or taking long-term steroids, should not receive live vaccines. Their healthcare provider may recommend alternative protection strategies.

- Healthcare workers and caregivers who are not immune should be vaccinated to prevent spreading the virus to vulnerable individuals.

Vaccination not only protects you or your child but also helps reduce community transmission, protecting those who cannot be vaccinated.

Post-Exposure Measures

If you or your child are exposed to chickenpox and not immune, contact your healthcare provider promptly. Receiving the varicella vaccine within 3–5 days after exposure can help prevent illness or reduce its severity.

For those who cannot receive the vaccine, such as pregnant women or immunocompromised individuals, a doctor may recommend varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG). This injection provides temporary protection by supplying antibodies that fight the virus.

If symptoms develop despite these measures, early antiviral medication may be advised for high-risk individuals. Monitoring for fever, rash, or breathing difficulties is important after exposure, especially in infants, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems.

Long-Term Effects and Related Conditions

After recovering from chickenpox, your body develops lasting immunity, but the virus that caused it—varicella-zoster virus (VZV)—remains dormant in your nerve tissue. In some people, it can reactivate years later as shingles. Understanding how immunity works and when to seek medical advice helps you manage potential long-term concerns.

Immunity After Chickenpox

Once you recover from chickenpox, your immune system typically creates lifelong protection against reinfection. This immunity develops through antibodies that recognize and neutralize the varicella-zoster virus if it reappears.

Most people who have had chickenpox do not get it again. However, individuals with weakened immune systems—such as those undergoing chemotherapy or taking immunosuppressive medication—may rarely experience a second infection.

Vaccination can also produce long-term immunity. The chickenpox vaccine contains a weakened form of the virus, prompting your body to build defenses without causing severe illness. Breakthrough cases can still happen, but symptoms are usually mild.

| Type of Immunity: Natural infection | |

|---|---|

| How It Develops | After recovering from chickenpox |

| Duration | Usually lifelong |

| Type of Immunity: Vaccine-induced | |

|---|---|

| How It Develops | After 1–2 doses of varicella vaccine |

| Duration | Long-lasting, may need booster |

Maintaining good overall health supports your immune system’s ability to keep the virus in check.

Shingles in Later Life

Even after you recover, the varicella-zoster virus stays inactive in your nerve cells. When your immune system weakens with age or stress, it can reactivate as shingles (herpes zoster).

Shingles causes a painful, blistering rash that appears on one side of the body, often the torso or face. Pain or tingling may begin days before the rash appears. Some people develop postherpetic neuralgia, a lingering nerve pain that can last for months.

Adults aged 50 and older can reduce their risk by receiving the shingles vaccine, which helps prevent severe illness and complications. If you suspect shingles, early antiviral treatment can shorten the illness and reduce discomfort.

When to Consult a Specialist

You should contact a healthcare provider if you or your child experiences unusual symptoms after chickenpox, such as prolonged fatigue, severe skin infections, or neurological issues. These could indicate complications that require further evaluation.

If you develop shingles, seek prompt medical care—especially if the rash appears near your eyes or if pain is severe. Early treatment with antivirals like acyclovir or valacyclovir works best within 72 hours of symptom onset.

People with weakened immune systems, pregnant individuals, or those taking immune-suppressing medications should also speak with a doctor. A specialist can assess risks, recommend vaccines, and guide preventive care to reduce future complications.

Vaccination Program

Explore our range of vaccination programs designed for your specific health needs.